Learning Activities

Interpretation Cards

Atikamekw Language Interpretation Story

Our history is an oral tradition. It’s hard to know exactly how things were before; it’s a story which we are told. The term I used to translate the word “history” is “atisokan”. “Atiso” means “to permeate”, such as when skin is dyed. We are talking about our history, the history of someone else, that which permeates it. “Ka wapisitc otatisokan” means “the history of others, the history of white people”.

I translate legend as “atisokan”, the same goes for “stories”; it’s the same for us. Legends tell a story. These are stories that have remained unchanged and have been passed on from generation to generation. It was through these stories that we survived. In the past, there was no television, no radio. It was through legends that children could come to know history. The same stories were always told to the same age groups and at the same time of the day. By repeatedly telling the same legends, the children retained them and came to be able to tell them in turn. Legends were told even if the child was asleep, because the child could still retain. I told certain legends to my son when he was five, today he is sixteen and he has not forgotten them. He will, in turn, be able to share them.

With only a few variations present, we can find the same legends in several nations. Such as the legend of “Tcakapec”, for example. He’s a character, somewhat like our savior. From one nation to another, his “image” will change; sometimes he’s a hare, sometimes a small soldier, sometimes he’s presented like a “real” person, and other times like a mythical character. On occasion, some nations hold one part of a story, and other nations hold another; some parts are common while other differ. It would be interesting to gather everything together to form a common legend.

For the founding myths, I add “kitci” to “atisokan”. “Kitci” means “something big, of great value”.A portion of the word “aniskowi” is used to mean “to bridge the gap to connect all things associated to something”; to make a connection to a topic. This is how we perceive “transmission” (aniskowictamakewin).

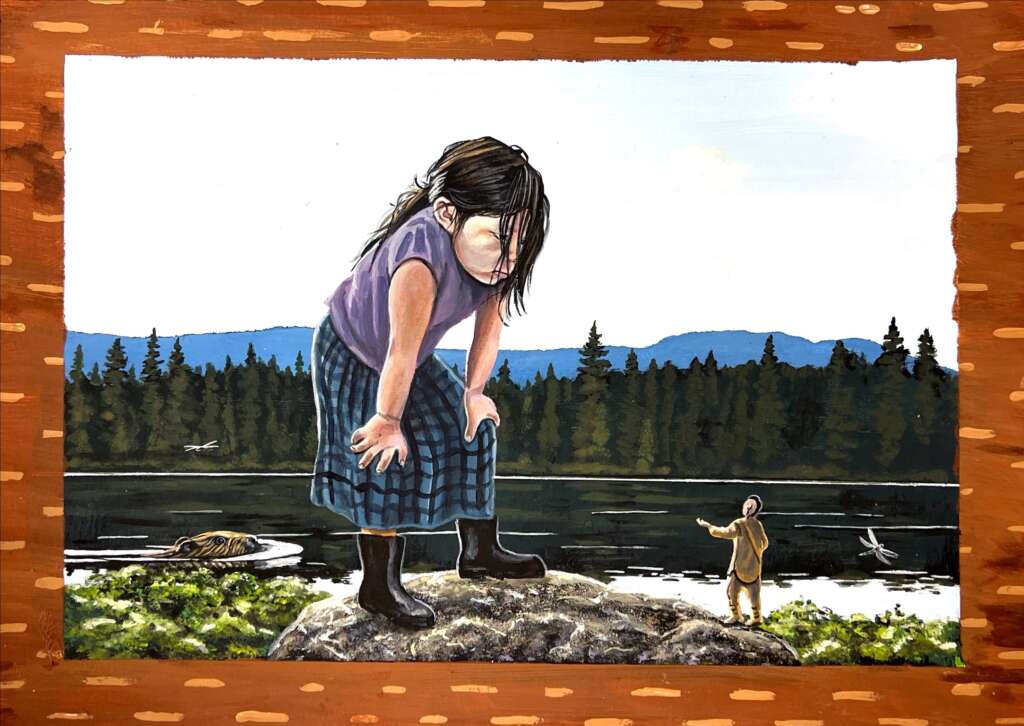

The bond between our nations and nature

Within indigenous thought, everything is connected. We are attached, connected to “notcimik”, which refers to nature, the forest, the territory. One can’t be separated from “notcimik”; we come from “notcimik”, we derive from “notcimik”, “ni otci” means “derive from”. All of the elements belonging to it are connected and form a whole; trees, animals, plants. This is why we consider that if the territory is perturbed, we are also perturbed. We also use the more general term “aski”. It’s also used to describe the earth. When we speak of “trapping territory”, we say “otatoskeaw aski”, “atoskew” referring to trapping. We can therefore consider that “notcimik” is within “aski”, it is part of the latter, more encompassing. We also use “nitaskinan”, which means “our territory”.

Hunter-Gatherer (Atoske Iriniw Mowiso Iriniw)

Initially, we’re all human, hence the use of “iriniw”, which refers to “the human being”. “Irin” is the root, the source, the origin, purity. “Iriniw” is the human of origin, the ancestry of humans. “Mowiso” is the action of picking, and “atoske” the action of hunting.

Respect between the hunter and the animal is very important. “Kicteritcikewin” is a mutual respect.

Spirituality

“Mantokasowin” consists of “manito”, which means “supreme being” and “kaso” makes reference to an action, to do something, to movement. “Kaso” is always associated to another component, as in “kicikaso” (someone who sets out to pay, “kici” referring to pay) or “mikaso” (someone who sets out to defeat another, “mi” referring to the battle). “Kaso” makes reference to movement, to action, something compelled by the supreme being which sets everything in motion.

To talk about these events called “Pow Wows”, we use the word “opwakanahanicimowin”, which includes “opwakan”, which could translate as “spirit”. We make the distinction between “soul” (“omanitom”, which refers to “Manito”, “supreme being”) and “spirit”. Each living being (each person, animal, plant, etc.) has its “opwakan”, its “spirit” sometimes also referred to as “little soldier”. In a “Pow Wow”, we invite all the “opwakan”, all these “spirits” from the animal world, from “the other side” (“deceased” people). They are invited to regain their strength, to come together, to dance; through this unification one obtains other energy. This is the meaning of the Pow Wow; allowing oneself to reconnect in order to revive all values, knowledge, etc.

The word “pipe” is similar; it is “ospwakan”. It is the instrument used to give thanks, to honor, to invoke prayer.

Between birth and death, life is but an accessory

We see life and death as connected, within the same infinite circle. When you are born, it also implies that you are going to die; you are born, you die. The drum is a symbol of this cycle of life and death; its beat is infinite; the rhythm of life.

The word “drum” is translated as “tewehikan”, but basically it’s a contraction. The true original word could be written “otewehikan”, but the “o” sound is absent in pronunciation, almost mute, hence the standardized spelling “tewehikan”. This brings to light the fact that this word includes the concept “otehi”, which means “heart”. The drum is therefore “the heart’s object” or “the heart’s instrument”, which also beats.

Often, words will be shortened, but in doing so, we also lose meaning. It is very important to properly say each word, each word’s morpheme, in order to protect the language, which is a legacy.

“We” is translated as “kirano”, “Being Together”. In our language, “kirano” refers to an all-encompassing whole; it is an inclusive “we”. We, as human beings, together, forming one entity; this is the concept of “kirano”. We all consider ourselves brothers and sisters in blood. We even tend to privilege others, before ourselves. When someone comes to my house and is hungry, it’s normal that they would go to the refrigerator and serve themselves, without having to ask for anything. It is also noticeable in the order of personal pronouns in our language; “kir” comes first; it is the second pronoun in English, the “you”, “the “Other”. The “I”, “nin”, follows. It is always the Other that takes priority, not self; the Other is more important than oneself.

The exclusive “we” is “ninan”, this “we” which refers to oneself among other people forming a group, which excludes others. In relation to the territory, one can therefore say “nitaskinan”, which is “our territory”, that of my nation but not of all nations, not of all humans; it is Nehirowisiwok territory (Atikamekw). “Our territory” which encompasses all humans, would rather be “nitaskino”.

In the past, with respect to survival, we were not dependent. We were structured, organized, able to take responsibility, able to do things for our survival. In short, we were autonomous; “ki mihitison”, “you are an autonomous being”, able of taking care of one’s own things. In the past, a woman could give birth alone.

It is important to remember the speed with which things have occurred. We had a territorial way of life. Then, very quickly, we were pushed to adopt another way of life. We experienced this as an expulsion; to be torn from, uprooted from one’s habitat.

Now, we have become dependent of so many things. An elder had already presented me with the following comparison: “today, we are like dogs, whereas in the past we were wolves”. He meant that a dog needs the help of man, it depends on him for his food; it must be taken care of. In comparison, a wolf is autonomous. They are organized in packs, with leaders. Today, like dogs, we have become dependent. We say “akosiwin”, which means “dependent” but with a connotation to sickness (it is a kind of “sickness” to be dependent), or “kitarimisin”, which means “to pity”.

In our way of looking at things, we do not fragment time; we do not cut it into pieces. When we think of a ruler, divided into millimeters, it corresponds more to linear thinking. Our thinking is rather circular, global. We do not feel pushed by the passing of time. We do not consider “taking too much time” or “not having enough time”, we do not count minutes when we do something. When we measure something, we consider accomplishments. We will consider “the action that has been accomplished”; this is our measure. The important thing is what needs to be done, which will take “the necessary time”; we will finish what we started anyways. It is the whole that is considered, the event. We measure according to the sum of achievements.

Language is a heritage that our ancestors have left behind; within it everything can be found. I want to share with you an excerpt from a statement given by an elder named Salomon (Sarmon) Dubé. “With all the hardships present in our communities, we must look back and try to find all of which our grandfathers left us. They have always well preserved thought, intelligence, the ability to see life; they have supported all of life. Do not be afraid to go back to the source, within our stories, in the old way of life. This is where you will find how you can improve your living. This is where you will find out who we are. This is also where you will find all our strength. It is within language that you will find all the strength to help you in your life, to get through the ordeals you will encounter. The language is ingrained with it; you only have to awaken it and use it. All of this has been left behind for us by ancestors.”

Not only could language name anything, but it could also mean many things at the same time. Through our language, it is like the earth is speaking; it is the language of Mother Earth. For example, if we talk about temperature, we wish to say that is it windy, “mirowew”, it could be translated as “we give you a breath of wind”. The language stretches that far, which is why it is important to preserve it.

Nicole Petiquay